Manifesto

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, The Muse: History, ca. 1865, Oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Faulkner basically got it wrong when he wrote in Requiem for a Nun that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

When I lived in New York after college, I used to spend most Saturday afternoons, when the weather was at least passable, reading in Central Park—sometimes sprawled out on the Great Lawn, other times on one of the benches just east of the Turtle Pond or on the north side of The Pool. I would walk down the elm-lined Mall on my way, and I would always stop for a moment by the statue of Fitz-Greene Halleck on the Literary Walk. I had, to be honest, never heard of Halleck before my first encounter with the statue, and yet, the dedication of the monument in 1877 was presided over by the President of the United States, his entire cabinet, and 10,000 spectators—so many people, in fact, who caused so much damage to the surrounding lawns, that the park’s leaders thereafter began to impose strict limits on the size of gatherings on their grounds. In this case, the past is not only past; it is undoubtedly dead.

It is evident that overall interest in the past—except perhaps as a vein of grievance waiting to be mined—has eroded to little more than a pebble in the stream of culture. A widely discussed article in the New Yorker recently lamented “the end of the English major” as only a miserly 7% of Harvard’s incoming class intended to concentrate their studies within the humanities. The Atlantic piled onto those concerns with a spotlight on “the elite college students who can’t read books.” A Columbia professor with whom the reporter spoke confessed that more than half of his students, when asked to name their favorite book, would once have chosen titles like Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre, but now cite contemporary young-adult novels like the Percy Jackson series, the 12-year-old protagonist of which features in a TV series on the Disney+ streaming service.

Those of us who care about history and deep literacy are losing the war. Can we at least win some battles? We are ceding share in the attention economy to social media and other digital entertainment products that people are choosing for good reasons—they are fun, and they are convenient. How can we learn from their success, improve and iterate on our own offerings, and meet our audience where they are with something that they will enjoy?

If we want people to shift more of our collective time toward rich and meaningful engagement with the past, we need to draw people in and give them a reason to stay. It sounds obvious, but the reality is that many of the people who should be our brand ambassadors and “influencers” actually do the opposite. When I was a freshman in college, I visited an archæology class during shopping week. The first slide of the lecture showed a picture of Indiana Jones, and the professor immediately turned on the cold shower: “If this is what you think of when you think of archæology,” he said, “then you’re in the wrong place.” It was, so I got up and left, and every year fewer and fewer people even get as far as that first slide. I get it—the reality of an archæological dig involves more dust-brushing than whip-cracking, and the typical find is more potsherd than Holy Grail—but that can come later. Once someone has been immersed in the sense of wonder that comes from understanding Hienrich Schliemann’s discovery of Troy or Hiram Bingham’s excavation of Machu Picchu, then the tactical details and nuances of the day-to-day work will seem more worthwhile. We won’t win if we make things boring before we make them interesting.

There is also, candidly, an excessively dry, somber, and sermonizing tone to much of today’s humanities scholarship, historical and otherwise. It is hard to imagine a worse sales proposition for a field than persistent, dour hand-wringing unmitigated by any awe or wonder. The travels of Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta, the conquests of Babur and Genghis Khan, and the voyages of Magellan and Columbus once fired the imaginations of scholars and citizens alike, moving generations of diplomats, soldiers, entrepreneurs, and travelers not only to deepen their studies of history, geography, philosophy, and politics, but even more exciting, to bring their curiosity with them into the messiness of the real world and to venture into realms theretofore unknown. The entirety of the human experience is in our domain—we have a lot with which to work! Narrowing our scope with grim, earnest moralizing and heavy academese will not inspire a growing audience.

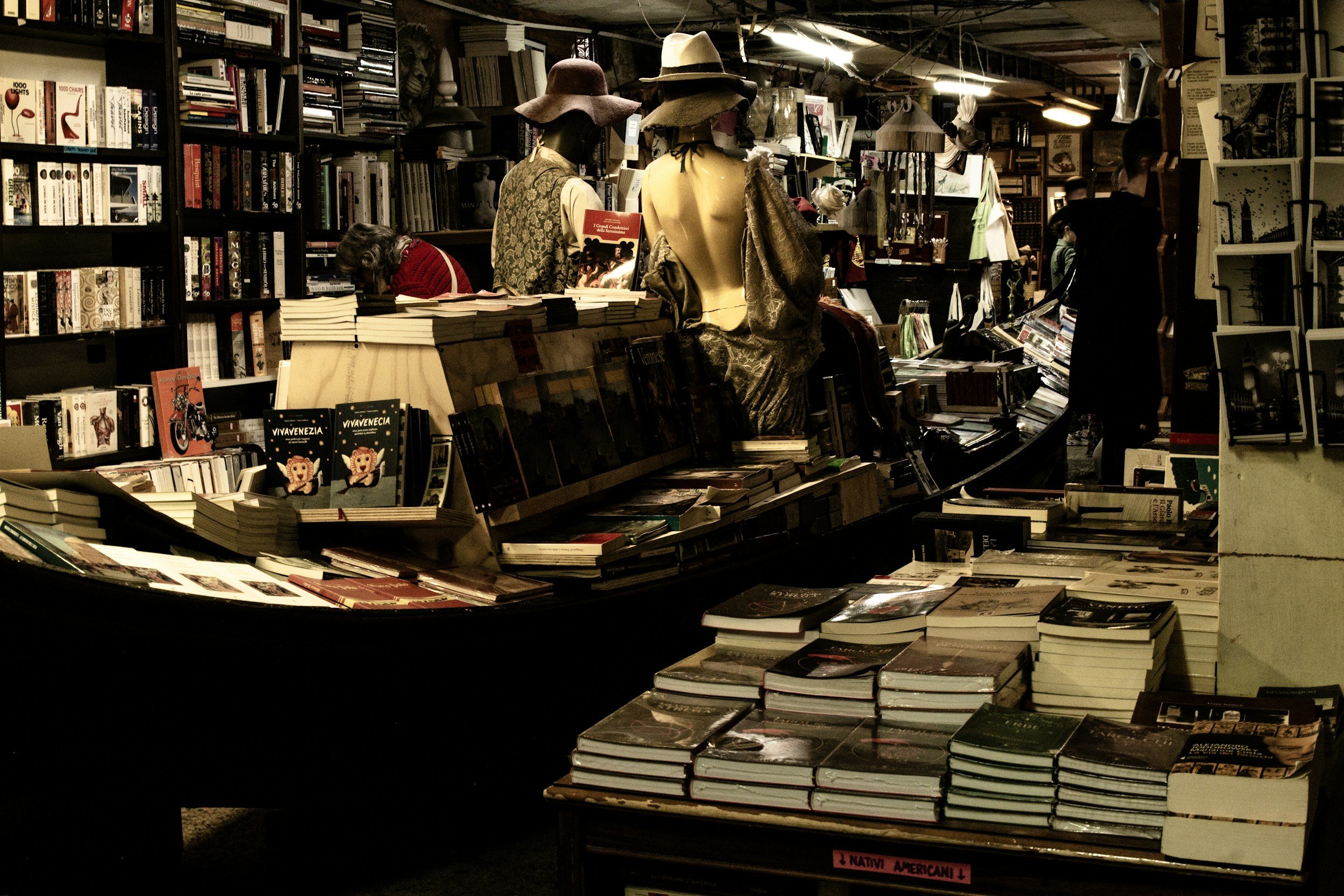

One of the greatest pleasures that I enjoyed during my school days as a historian-in-training were when, deep in the stacks of the library’s sub-basement, where the air smelled faintly of vanilla and the lights would turn off if you sat still too long, I would pull a book from the shelf, one that may not have even been checked out for decades, and I could find myself face-to-face with an emissary from the past—whether a famous conqueror or an obscure figure whose name was then as unfamiliar to me as Fitz-Greene Halleck. The ghosts of these books were people from whom I might be able to learn, who could provide a view into a (perhaps) vanished world or an obsolete perspective, and with whose words I could grapple through deep immersion, critique, and judgment. Sometimes these authors would point me in the direction of others from their time or before, as I scoured their bibliographies for my next destination in the stacks. It was not necessarily a comfortable or an easy experience, but then rarely are comfort and ease the greatest sources of pleasure. It was an odyssey of the intellect, and it was rewarding.

It was in reflecting on those experiences of deep reading and serendipitous discovery that we were inspired to create Ozymandian Editions and to contribute our efforts to the renewal of reading in general and engagement with the voices and primary sources of the past in particular. Our initial scope will focus on the most lively and intriguing books that one could encounter on the shelves deep in those library stacks—works including memoirs of exploration, novels of wartime espionage, and disquisitions on philosophical ideas that shaped their eras but are neglected today. Over time, we look forward also to introducing lively, transportative, and thought-provoking new works by contemporary authors to our list. We hope to iterate, too, on the way that we deliver our content, with the goal of delivering fresh and intriguing user experiences with the potential to grow our audience through new channels and in new places (not only dusty basement stacks, however much we like them!) It is our great hope that we can build a community of people who will discuss, debate, and of course, enjoy the richness of our history and culture together, both in person and on social platforms—some battles must be fought on that terrain too!

We hope that you will join us for the adventure.